Why are references important?

One element which distinguishes university research – academic or scholarly or scientific work – from other kinds of research and writing is the citation of sources. In applied linguistics, for instance, we rely on research in education, psychology, and linguistics to inform our own research and we summarise, synthesise, and quote articles and books in these fields to support our arguments. We use definitions of key terms which have been agreed on by previous researchers, we make claims about what we know which are supported by earlier research, and we aim to build on these earlier studies in our own work.

As academics and university students and perhaps future teachers, we aim to ensure the quality of our research by careful reading and reporting of good work by good researchers published in good journals. Often this means peer-reviewed articles and books written by university faculty with established publishing houses.

How does peer review work?

In order to publish an article in a reputable academic journal, researchers submit their work to the journal’s editors, who are usually university faculty. If it is suitable, the paper is sent out for review by two or three other academics, who submit written reports recommending revisions or indeed rejection. Revised papers are then edited for publication. This process is called peer-review, and is usually anonymous and unpaid work. Authors, reviewers, and editors often draw salaries from schools and universities for teaching and research but do not receive payment for writing articles which are published in journals, or reviewing or editing these articles. Nevertheless, the peer-review process is considered essential to control the quality of published research.

This kind of peer-review is conducted by all major journals: see for example an overview of journals publishing research on teaching and learning second or foreign languages, an important area of applied linguistics.

What’s not to like?

Unfortunately our current academic publishing model has two drawbacks. First, this quality-controlled content is usually NOT free or open access. Articles are paywalled, meaning that readers or institutions like university libraries have to pay publishers to access research. This means these articles are simply not available to the academic community of university lecturers and students. Many consider the academic publishing model to be irretrievably broken, since it relies on the unpaid labour of academic editors and reviewers, while providing revenue for large publishing houses such as Elsevier and Springer.

A second problem concerns a parallel publishing system which has emerged in the form of predatory journals. These journals have names similar to the major established journals, but do not control quality through peer-review. Instead authors simply pay a publication fee to have their work accepted. These articles are easy to find and free to read online but generally do not meet academic standards for good scholarship. Some critics see these journals as a response to the ‘publish or perish’ injunction, that is, increased pressure on academics, perhaps especially in developing countries, to produce evidence of research to justify recruitment, promotion, or funded projects.

Difficulties in reading academic journal articles

Due to the current situation in academic publishing, there are two problems for students, teachers, and researchers in applied linguistics:

1. to distinguish good research published in established journals which use rigorous peer review from lower quality work which has not been reviewed and revised in this way

2. to gain access to research which has been published behind paywalls and thus require readers or institutions to pay fees to publishers for access to full articles.

In the following pages I offer some guidance for identifying appropriate articles, gaining access to full versions of papers, and then using these references correctly in your own work. I work from the position that neither students nor academics should consider spending their own money to fulfil academic obligations.

Finding good articles

A good place to start looking for articles is the reference list of an article you already have. Read the literature review section of the paper to identify relevant articles and authors, then look them up on Google Scholar (scholar.google.com). This specialised search engine can help identify research articles and books and has a number of useful functions.

1. Search by keyword

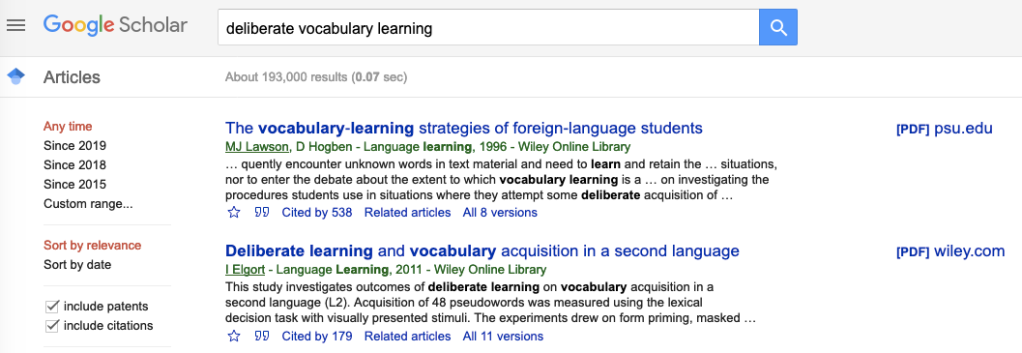

If I want to see research into how learners can memorise L2 vocabulary deliberately (as opposed to picking it up incidentally) I can type “deliberate vocabulary learning” into Google Scholar.

This search shows articles in this area with the name of the journal and the date, so I can immediately see if it is a reputable journal and whether the article is recent. We are often interested in more recent research, and there’s a filter on the left where you can set a date limit or range.

This search also gives names of authors under the titles. If a name is underlined I can click and check the author’s profile (academic affiliation, other publications). Otherwise I can still use the name in Google Scholar to look for other work by this author. I might be interested in Irina Elgort, the second hit in my initial search, since she has a recent paper (2011) in a good journal (Language Learning).

2. Search by author

Here you can see a list of publications by Irina Elgort, which you can filter by date (left menu). On the right are direct links to PDF versions of the papers where these exist, though you need to click to find out whether you can access the paper freely or whether there is a paywall.

ResearchGate is a social network for academics where researchers share their work, so it is worth a click on these links to see whether a paper is available there. Sometimes these papers are pre-publication versions which are not formatted for journal publication and which may not include revisions undertaken during the peer-review process. This means you can trust the information but should not quote directly in your own work because you’re not using the ‘version of record.’

3. Search for related articles

Use the links under each article entry on Google Scholar to see which other articles have referenced your article (Cited by) and articles on the same topic (Related articles).

You can also visit journal homepages and search their content for your keywords. There’s a Wikipedia list of applied linguistics journals here and I have a blog post on instructed second language acquisition (ISLA) journals.

You should be cautious about predatory journals which are not on these lists and generally avoid articles from these journals since they do not use rigorous peer review.

Adopting good habits

I recommend separating the hunt for articles, which can be quite fun, from actual reading, which is also rewarding but requires a different kind of concentration. You will need several cycles of reading, looking for new sources, and reading again before you can be sure to have found enough key work.

I also recommend saving articles methodically in folders and making a Word file with the APA citation for each. Use a citation manager such as Zotero by all means, though if you have never used one it may not be worth the investment of time and energy.

Your reference list will include all and only work that you actually mention in your paper (either with an actual quotation or simply discussion of the work). However it’s hard to tell which papers you will end up using, so it’s best to save each PDF and the APA reference. You can always remove a reference later.

Use Google scholar (scholar.google.com) for a copy of the reference: click on the quote marks under the title and copy the APA style option.

Accessing full papers

Once you have identified an article you wish to read, there are a number of ways to access the paper. Sometimes you will be lucky and the article you want is published in a good open-access journal. Remember we do not recommend open access journals which do not use peer review (predatory journals) since there is no guarantee that this research has been rigorously conducted and carefully written up. However some journals do have good peer review and are also open access, meaning that all their papers can be freely accessed without paying, as soon as they appear, and for an unlimited period.

From this you can infer that other journals offer articles which can be accessed a) if you or your institution pays, b) after a specified period of time (called an embargo, often a year), or c) for only a short time, after which they are paywalled.

1. Open access

Language Learning and Technology is an excellent online journal for computer-assisted language learning (CALL) and all its papers can be freely accessed a) without paying b) as soon as they appear and c) for good.

Another possibility is that your paper is in a paywalled journal but freely available. This can happen sometimes when a new paper appears, in which case the paper will only be accessible for a short time, or when the authors’ institution has paid extra to make the article free for good.

If this is the case for the paper you want, just ‘take the money and run’: download the PDF and save it. If not, the next best option is institutional access via your university.

2. University access

If you are working on a computer on campus or logged into your university account from elsewhere, you will have access to all articles and journals for which the university has a subscription. (University subscriptions are somewhat complicated and tend to change, so I recommend a ‘suck-it-and-see’ approach rather than trying to work out which journals the university is subscribed to.)

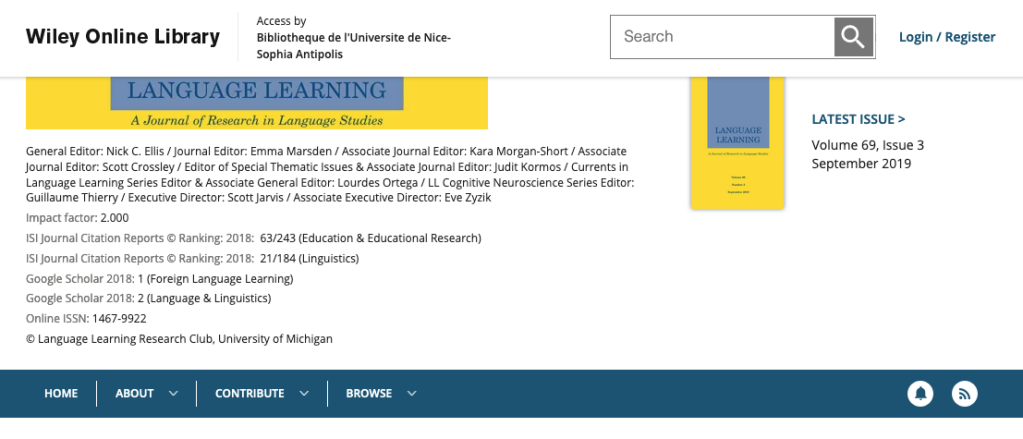

A click on the title of the Elgort (2011) paper will take you to its page on the journal website. The screenshot below shows I am identified as a reader at Bibliotheque de l’Universite de Nice-Sophia Antipolis and that I have ‘full access.’

This means I can click on the PDF and download the paper, and I recommend always doing this in case you lose access on a return visit.

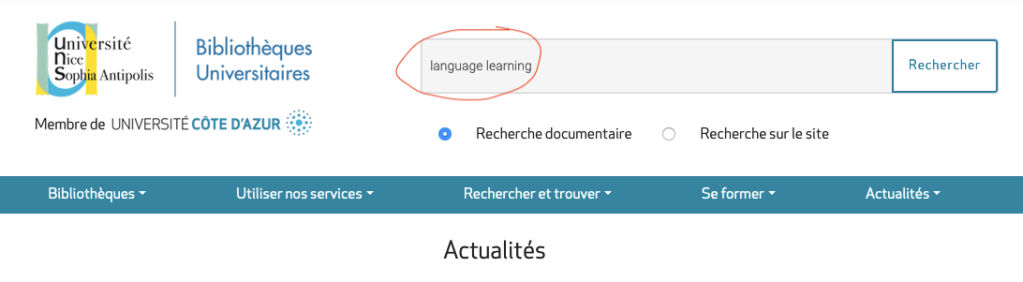

You can also start from the university library at https://bu.univ-cotedazur.fr

In the search box type the name of the journal: here I want Language Learning

Click through to online access if available and search the journal by author name or volume/issue.

3. Last resort

As noted, your options for accessing full journal articles which are not open access are as follows

a) Access via the university library, typing in the journal name and checking from this starting point

b) Look on Google, Google Scholar, and ResearchGate or Academia.edu to see whether authors have posted copies

Failing this it is perfectly possible and quite acceptable to contact the author as follows …

c) E-mail the corresponding author, whose name and e-mail usually figure on the page of the journal’s website with the title, authors, and abstracts. Authors are generally very happy to oblige since everyone likes their work to be read and possibly cited.

Dear Professor X

I am a student in English at the University of Nice working on [topic] and I came across your article [title] published in [journal] in [year]. Our institution does not have access to this journal and I wonder if you would be willing to share an electronic copy with me.

Sincerely Y

Citing references

Academics, scholars, and scientists have different conventions regarding how they refer to articles and books published in their disciplines. The rules are given in style guides, and different journals use different styles.

Two aspects are important:

1. how to refer to someone’s work in the body of your own writing, often called in-text or inline citation,

2. how to list your references at the end of your paper.

Some styles involve giving the full names of authors and the titles of their work in your own text, and others use footnotes for references. Reference lists are always ordered alphabetically by author last name, but conventions regarding the use of quotation marks, capitalisation, italics, and parenthesis are highly codified and differ across styles.

In applied linguistics we frequently use APA style. In-text citations require only author last name and date (e.g., Elgort 2011), while the reference entry has last name, first initial, date, title, journal. You can find information about APA style online or you can simply copy from any recent APA article. You can also click on the quote marks below an article listed on Google Scholar and copy-paste the APA format, though you should also check for accuracy and completeness.

Happy hunting!